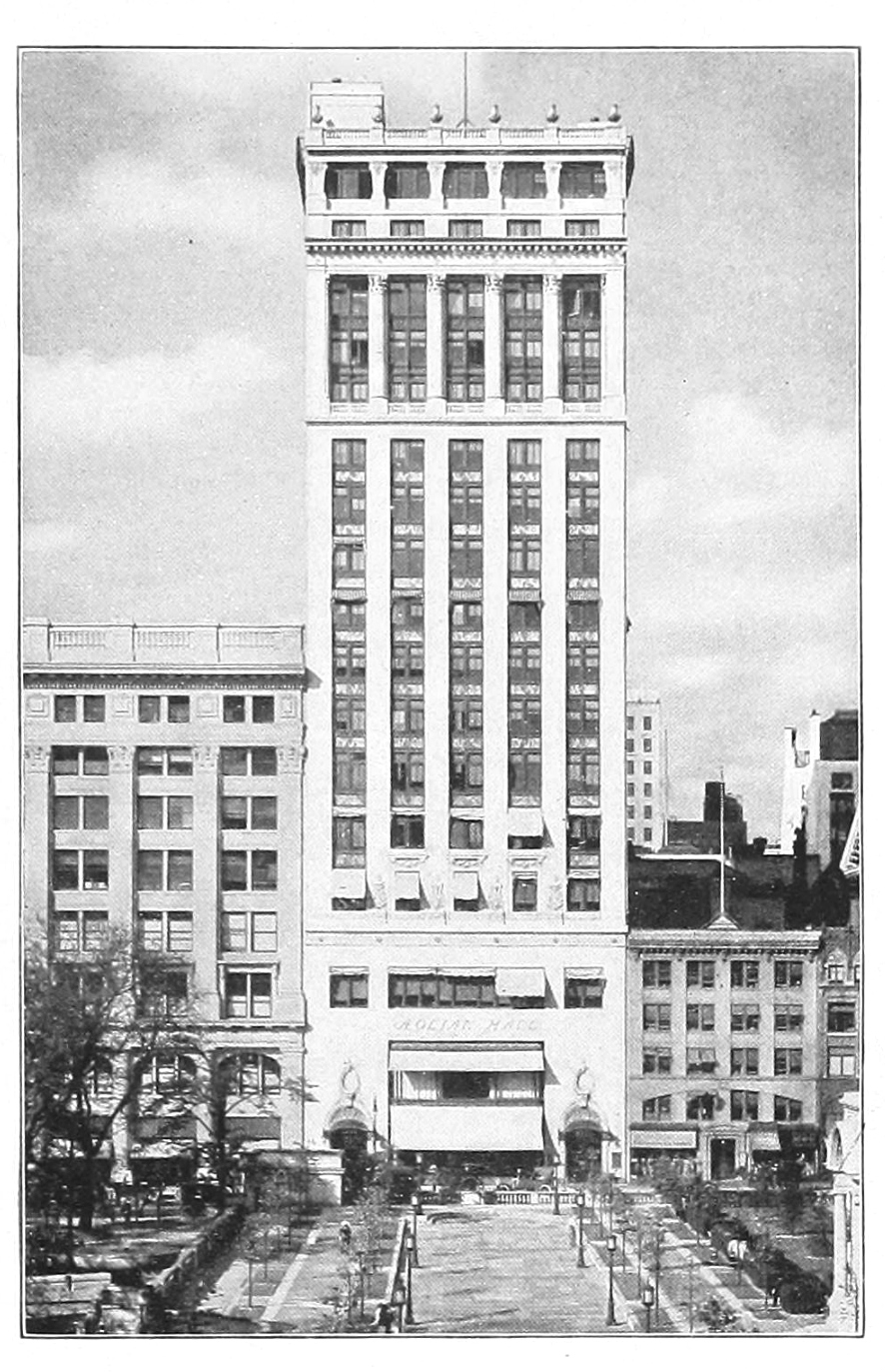

Aeolian Hall 1916

Before the Show

Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12, 1924, New York City

February 1924 was a month chock full of historical events, both large and small. Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States, died on the 3rd of February. Later in the month, the British India government released nonviolent activist Mahatma Gandhi early from prison for “reasons of health.” (He was two years into his six-year sentence.) On the 17th and 24th, Johnny Weissmuller (aka Tarzan) set two Olympic records for swimming. Academy Award winner, Purple Heart recipient, and Silver Screen star Lee Marvin was born on the 19th in New York City. And, on the 22nd, Calvin Coolidge became the first president to deliver a radio broadcast from the White House in honor of George Washington’s Birthday.

That sure was a lot of goings-on for the second month of 1924. But the 12th of February was a real standout day. Don’t get me wrong; I am not referring to Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus, which was opened on February 12th in Egypt, revealing his now-famous solid-gold mummy case—nor the Broadway opening of the show Beggar on Horseback at the Broadhurst Theatre on 44th Street on that very day.

Even more exciting than seeing King Tut’s tomb or Tarzan winning gold medals is an event that stands out from them all. On Tuesday, February 12, 1924, while all of America celebrated Lincoln’s Birthday, Aeolian Hall on 42nd Street in New York City hosted the première performance of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue—the song that would herald in “The Jazz Age” and “The Roaring Twenties.”

The producer of the concert was none other than the “King of Jazz” himself, Paul Whiteman, who dubbed the concert, “An Experiment in Modern Music.” To drive home the “experiment” angle of the concert, Hugh C. Ernst, Whiteman’s business manager, wrote in the Aeolian Hall event program, “The experiment is to be purely educational.” Ernst continues about Whiteman’s orchestra, elucidating that jazz had gained popularity in America and influenced young people to start scoring and composing: “These same people are creating much of the popular music of today. They are not influenced by any foreign school. They are writing in the spirit of the times. They are striving only for melodies, harmony and rhythms which agitate the throbbing emotional resources of this young restless age.”

In an unprecedented declaration, a January 4th article in the New York Herald Tribune whooped, “Whiteman Judges Named: Committee Will Decide ‘What Is American Music.’” It then continues, “Leonard Libeling, editor of The Musical Courier, will be the chairman of the critics’ committee…composed of the leading musical critics of the United States.”

The “educational experiment” had morphed into a sort of 1920s version of an America’s Got Talent concert with all the trappings, including (of all things) a panel of “judges.” This is thanks to the crackerjack Paul Whiteman PR machine. The critics were invited to figure out exactly what the heck “American Music” is. Good luck with that!

The concert was designed as a caucus between the low-culture jazz denizens and the high-culture 1% elites in their sacred hallowed tabernacle, Aeolian Hall. Whiteman’s PR machine went into hyperdrive feeding the media frenzy.

Because the event was scheduled on Lincoln’s Birthday, some in the mainstream media baptized the concert, “The Emancipation Proclamation of JAZZ.”

Paul Whiteman explained in his book Jazz, “My idea for the concert was to show these skeptical people the advance which had been made.” Just for the record, the “skeptical people” Whiteman was planning to “show” was the 1% music and cultural elites. Musicologist David Schiff described Paul Whiteman as a man straddling both sides of the cultural chasm, calling him, “a sophisticate and a lowlife, a Westerner who epitomized New York, a creator and explorer, a classically trained violinist who functioned more as a manager and promoter than as a musician.”

Music critic Henry O. Osgood wrote in his book, So This Is Jazz, that the concert was, “The very first step toward the elevation of jazz to something more than the accompaniment for dancing. It was the first concert of its kind ever.” Because the event was scheduled on Lincoln’s Birthday, some in the mainstream media baptized the concert, “The Emancipation Proclamation of JAZZ.” Gershwin biographer Isaac Goldberg declared, “Slavery to European formalism was signed away.”

While Whitman’s intentions were depicted as “Trying to make an honest woman out of jazz,” which referenced the early years of jazz and its roots in the New Orleans brothels. Deems Taylor, critic for New York World, furthered the low-culture/high-culture rift when he opined, “Jazz was ready to come out of the kitchen and move upstairs to the parlor.”

Some in the media held a pessimistic view of the enterprise, rebranding the “Experiment in Modern Music” as “Whiteman’s Folly.” While others exclaimed, “Gershwin was breaking his neck trying to starve to death.” In fact, the Program Notes for the concert tour quoted Gordon Whyte:

“Yes, Jazz is SAVAGE! Everyone says Jazz is savage in motive and savage in texture. In fact, some pundits would have it that it is composed by savages for savages.”

Even Paul Whiteman joined in with the doubters: “The idea struck nearly everybody as preposterous at the start.”

The cultural aristocracy’s holy scripture, The Musical Courier, declared in an article, “Jazz at its worst…usually perpetrated by players of scant musical training who believe that random whoops, blasts, crashes and unearthly tom-toming is something akin to genius.”

Esteemed cultural critic and clairvoyant prognosticator Gilbert Seldes wrote in his book, The 7 Lively Arts, about his recollection of the time. He said, “Gershwin is capable of everything….I feel I can bank on him.” Indeed, Seldes was “banking” on Gershwin to deliver the goods on February 12, 1924, and from what we know today, Gershwin did just that.

Click here for “An Experiment in Modern Music—Part 2” An insiders view of the concert.

Leave a Reply